Foundations of Care

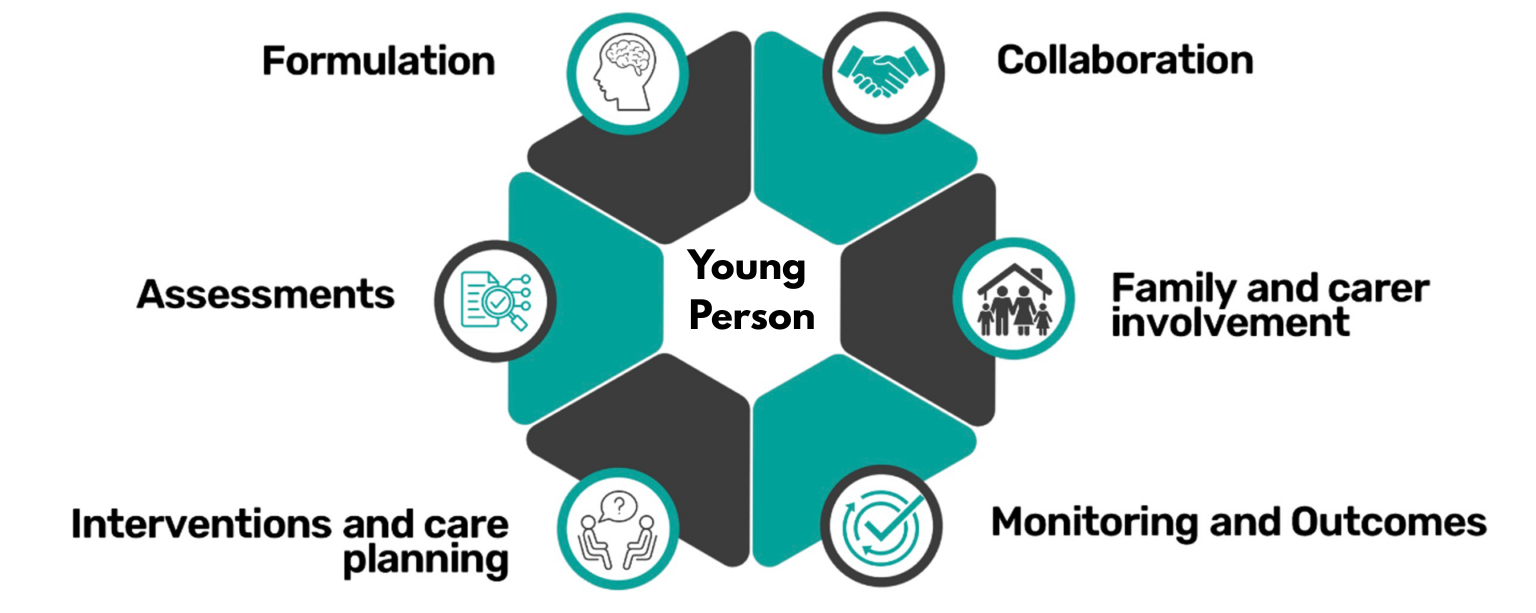

Each young person referred to Care in Mind receives a robust and holistic needs assessment; supported by a psychologically informed formulation of presenting needs and treatment goals.

Care is underpinned by a range of evidence based models, and a full range of clinical interventions delivered by highly trained specialist staff teams; including Psychiatry, Clinical Psychology, Specialist Nurses, Psychotherapies, and complementary therapies.

In our specialist residential homes our Registered Managers lead teams of highly trained specialist support staff who work in collaboration with the clinical MDTs, young people and multi-agency partners. These teams are also supported by evidence based systemic interventions delivered by the clinical team.

Partnership & Collaboration

Each young person is encouraged to work in partnership with Care in Mind staff and the multi agency partners involved in their care. Young people will collaborate on care planning, risk management, and treatment goals. Outcomes are measured regularly and reviewed with young people and our multi-agency partners to support onwards care planning.

Through a trauma-informed, least restrictive model of care, underpinned by a therapeutic risk management approach, we support young people in achieving their recovery goals and moving on into independence.